World History

As the opening two phases of the grand cultural and intellectual rebirth (literal meaning of the French term Renaissance) of the late medieval period, the Italian Renaissance, or Quattrocentro (Italian for 1400s), and early northern renaissance sparked tremendous achievements in literature, art, architecture, and music that were inspired by creative interaction with rediscovered sources of classical antiquity. Launched from Florence, the Italian Renaissance concentrated its energies in the northern regions of Italy before moving south to Rome, where its spirit was embraced by the Renaissance popes.

It reached its zenith in the late 15th century prior to its dissolution, aggravated both by an ecclesiastical backlash against its perceived secularism and sensuality and by the series of Italian Wars, or foreign invasions against Italy, starting in 1494. The Renaissance fervor was not to be extinguished, however, as its ideals migrated northward to France, then to the Low Countries and Germany, and finally to England and Scandinavia by the close of the 16th century.

Most common people of the time were unaffected by these innovations and did not view their age as distinctive. Producers of its main aesthetic streams, such as authors, artists, and their patrons, willfully rejected the culture of the preceding era (the Middle Ages) and set out to create a new one.

Sensing only a limited attraction to the courtly motifs of the medieval secular literary tradition and disillusioned by the elaborate argumentation of Scholasticism, the sophisticated urban ruling classes searched for a new culture that would enable them to cope with the quandaries of human existence and empower them to deal with and even manipulate other people.

Perfectly suited for this aim was the literature of ancient Rome, with its strongly political and ethical outlook and the prominence it placed upon oratorical and rhetorical training. To gain a deeper understanding of Latin literature, the urban elites were quickly drawn to the Greek literature that Roman authors frequently cited and presupposed of their readers as background knowledge. Hence the classical Latin and Greek texts of antiquity served as a common springboard for the era’s multifaceted and interdisciplinary cultural shift.

Social Origins

While formally beginning in the 15th century, the social origins of the Italian Renaissance can be traced back to the economic, social, and political developments in Italian society during the 12th through 14th centuries. The 12th and 13th centuries comprised an age of expansion and prosperity directed by the capitalistic noble classes, or grandi, who often resided in the cities and invested in business but whose cultural traditions were military and feudal, giving preference to the chivalric and courtly literature of France.

This changed in the late 13th century when the nonnoble classes, led by rich businessmen, seized control of many town governments and drove the grandi from power. However the 14th century experienced a series of disasters that, paradoxically, modified the structural foundations of Italian society so as to promote the flourishing of artistic and literary endeavors.

Amidst the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, King Edward III of England disclaimed his debts in 1345, leading to the collapse of the two largest Florentine banks, owned by the Bardi and Peruzzi families. From 1347 to 1350 the Black Death, or bubonic plague, exterminated one-third of Europe’s population, which triggered an economic depression followed by a lengthy period of stagnation. While these events prevented the founding of new fortunes, they left the wealth of established rich families largely intact, creating a new social condition.

Since the relatively high degree of social mobility that kept business enterprise open to new talent and preoccupied with acquiring new wealth had evaporated, the dominant business class was converted from a group of self-made men to a group of men who had inherited their wealth and who had been raised in luxury that they intended to preserve but they could largely take for granted.

Rich businessmen, who retained their active participation in politics to defend their material interests from radical movements spawned by working-class agitation, now devoted an equal amount of time to public affairs, especially the patronage of art and literature.

Looking to Greco-Roman antiquity as a model of administrative effectiveness and intellectual genius, the thinkers, writers, and authors of the age, collectively known as humanists, founded a new approach to scholarship, the mission of which was to restore “true†civilization in place of the prevalent “barbarous†civilization.

This view of history was spearheaded largely by Petrarch (1304–1374), who proceeded to synthesize it with his new anthropology, or doctrine of humanity, that humans were rational and sentient beings, intrinsically good by nature, with the power to think and choose for themselves. With this blatant denial of the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, the humanists provoked fresh insights about reality that questioned the church’s philosophical perception of the universe and the role of humanity within it.

Before the 13th century, Italian was not the language of literature in Italy, as most works were composed in Latin, French, or Provençal. However, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries before the rise of Renaissance humanism, a number of masterpieces in the vernacular catalyzed the transition of Italy from a cultural backwater to the leader of European culture.

The nation’s first great literary figure, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), wrote his magnum opus, La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy), in Italian, which reflected the social and political life of the Florentine people and amassed great popularity.

Petrarch became the second great figure of Italian vernacular literature through poems capturing the attention of both refined courtly society and the common people. The master of the Italian sonnet, Petrarch is best remembered for his highly personal and subjective love poetry, most notably the Canzoniere, a collection of sonnets addressed to his unrequited love, Laura.

The third great figure of 14th century Florentine literature was Petrarch’s disciple, Giovanni Boccacio (1313–75), whose principal work, the Decameron, featured 100 stories recounted by 10 storytellers who fled to the outskirts of Florence to evade the Black Death. His work was heightened by motifs reflecting everyday life, including satire against corrupt clergymen, amusing treatment of human idiosyncrasies, and tales of marital infidelity.

Unfortunately the trend toward classical humanism in the first half of the 15th century temporarily stifled the germination of the vernacular tradition, which deterrence was removed by the major revival of the vernacular in the second half of that century.

Under the influence of Florence’s leading family, the Medicis, Italian resurfaced as a medium for important literary work and came to the fore when Lorenzo de’ Medici, the first of the family educated from an early age in the humanist tradition, formalized Medici rule over the city with his creation of the new Council of Seventy, over which he appointed himself head, in 1469. Lorenzo was a lyric poet of great ability who set the stylistic parameters for both secular and religious poetry in the vernacular.

The Florentine Petrarchan tradition experienced great development under the Venetian cleric Pietro Bembo, a leader in the movement attempting to restore the purity of the Latin language embodied in Cicero, when he embraced its highly refined sentiment and technical mastery of intricate verse forms for his Italian poetry.

Popular literature of a less aristocratic flavor often applied French chivalric and courtly themes to Italian characters. Recasting the French heroic knight into the Italian Orlando, Italian courtiers such as Luigi Pulci (1432–84) adapted this material for consciously humorous verse.

Medieval French chivalric themes were discussed more seriously in the poem Orlando innamorato (Orlando in Love) by Matteo Boiardo (1441–94), a noble at the refined court of the dukes of Ferrara who invented a new style integrating humanistic classical topics with medieval chivalric interests.

This style received further advancement under Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533) in his Orlando furioso (Orlando’s Insanity) and reached its pinnacle in the 16th century with Torquato Tasso (1544–95), whose Jerusalem Delivered, an epic of the Crusades, revamped this popular medieval theme into a major literary production that influenced practically all other 16th-century literature.

The most brilliant example of Italian prose in the High Renaissance (the early 16th century) is the work of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) on politics and history. His two principal books, The Prince and Discourses on the First Ten Books on Titus Livius, drew heavily on the author’s firsthand experience as a leading Florentine diplomat and civil servant in the Florentine republic (1494–1512).

Although The Prince is notorious for its advocacy of political self-seeking through deceitful tactics, Machiavelli regarded a balanced republican government, typified by Rome, as the best and most durable form of government and trusted the public spirit and wisdom of the common citizens more than that of princes and aristocrats.

In the artistic sphere, Giotto di Bondone (1266–1336) took the first steps toward the Renaissance, completely forsaking the flat and nonrepresentational appearance of the prevailing Byzantine art in favor of the illusion of three-dimensional form on the twodimensional painted surface.

He was the originator of “tactile value,†portraying his space as an extension of the real space out of which the spectator looked and giving his figures a three-dimensional depth that appeared as if the spectator could reach in and grasp them. Moreover, each of Giotto’s works features the visual representation of one unifying idea instead of a spectrum of meticulous details.

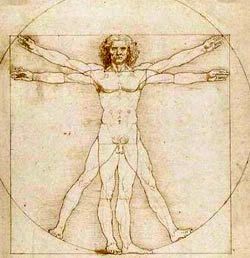

The Renaissance style in sculpture was created by Donatello (1386–1466), who assimilated the basic principles of ancient sculpture, such as contrapposto (with weight shifted to one leg) and the unsupported nude, into a framework creating the appearance of movement and furnishing accurate anatomical structure of his figures.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) brought this style to maturity with sculptures independent of any surrounding architectural support, including the David and the marble figures he carved for the tomb of Pope Julius II at Rome and for the tombs of the Medici family at Florence.

The striking aspect of his approach is its portrayal of robustness and monumentality in the human body, often styled “Dionysian†after the Greek god known for his unbridled power. His spectacular frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel stand as perhaps the single greatest work of High Renaissance painting, and his redesigning of St. Peter’s crowned his prominence as an architect.

Two other Florentine-trained artists, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520), further defined the High Renaissance style. A universal genius with interests in nature, physics, and engineering, Leonardo is most renowned as a painter, revolutionizing his field with the invention of both atmospheric background and sfumato, the “smoky†effect achieved by blurring the outlines of figures to make them softer with an environment of shadow tones. He experimented greatly with new paints even at the expense of the traditional fresco style, seen most prominently in The Last Supper.

Intensely interested in studying the human personality and portraying it on canvas, Leonardo attempted to capture the fragile, fleeting, and illusive qualities of human facial expressions in his Mona Lisa and Virgin and Child with St. Anne. His plans and sketches proved greatly significant for architecture, as they constitute the blueprints for buildings later erected by his friend Bramante (1444–1514).

Raphael’s images, including his many Madonnas, the School of Athens, and Disputa, rank among the world’s most beloved artistic treasures and are noteworthy for their sense of peace and serenity. Furnishing inspiration in architecture as well as in literature, the ideals of classical antiquity experienced restoration in the work of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72). Brunelleschi’s designs for two Florentine churches, San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito, reflect his intense study of ancient Roman buildings, as both employ the early basilica form and classical columns.

Further he is renowned for his discovery of the mathematical rules of perspective and his innovations in shape, seen most clearly in the octagonally designed dome base for the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Alberti revitalized the ancient brick architecture of Roman times, as portrayed by his San Andrea church in Mantua, and established the Renaissance standard use of flat roofs, overhanging cornices, and prominent horizontal lines.

Ironically 15th century music saw little advancement and primarily continued in the genres conceived by Francesco Landini (1325–97), who despite his blindness from childhood became a leading composer and music theorist. Celebrated as a composer of secular works for voice and accompaniment, Landini developed the ballata, or rhythmic dance song; the caccia, a “chasing†song of enjoyment; and, most importantly, the madrigal, a high art form in which poetry was sensitively set to music and so guaranteed that the music would serve as an appropriate vehicle for conveying the spirit and emotional content of the text.

Italian Renaissance church music reached its zenith during the 16th century in the works of Giovanni da Palestrina (1525–94), choirmaster of St. Peter’s in Rome, who composed more than 600 religious pieces, including 102 masses. Typified by the Agnus Dei from his Pope Marcellus Mass, Palestrina achieved a stunning sense of serenity in his works through balance, purity, and arrangement of texts that made the words clearly understandable during performance.

Early Northern Renaissance

With the free exchange of scholars and students between European universities and political exploits, such as the French invasion of Italy in 1494, which brought new contact between cultural elements, Italian concepts and discoveries were reaching into the rest of the Continent by the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The reorganized and powerful monarchies of the north quickly found that Renaissance thought suited their needs, as its endorsement of social class and military prowess enhanced their status, and its emphasis on public service, personal merit, and learning furnished an attractive substitute for the traditional manners of the uneducated and disorderly feudal classes.

Moreover, the invention of the printing press at Mainz by Johann Gutenberg in 1456 changed the course of history by making possible the rapid dissemination of ideas to a populace moved by the spirit of the age to become increasingly more literate.

Disillusioned by corruption in the late medieval church, including simony (buying and selling of church offices), sinecures (receiving the salary from a benefice, or region to be served by a clergyperson, without overseeing it), pluralism (holding more than one office), clerical concubinage, and the selling of indulgences, the bourgeoisie or rising upper-middle class of merchants found the Renaissance rejection of the recent past and the desire to return to the original sources of antiquity tremendously appealing.

This interest sparked a northern movement of biblical humanism, which exalted ethical and religious factors over the aesthetic and secular ideals typical of Italian humanism and was primarily interested in the Christian past, or Judeo-Christian heritage, rather than the classical Hellenic heritage of Western Europe.

More interested in the human being as a spiritual than a rational creature, these biblical humanists applied the techniques and methods of humanism to the study of the Scriptures. This exegetical approach was spearheaded by John Colet (1466–1519), a pious English cleric who, after visiting Renaissance Italy, soon afterward began in lectures at St. Paul’s Church to expound the literal meaning of the Pauline Epistles, a novelty because former theologians interpreted Scripture allegorically with an almost total unconcern with the meaning originally intended by its authors.

Borrowing his notion of biblical humanism from Colet, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469–1536) became the greatest of all the northern humanists and an internationally renowned scholar. Unlike the later reformers who vehemently denounced the evils in the church, Erasmus’s scholarly spirit inclined him to oppose its abuses through clever satire in his The Praise of Folly (1511) and Familiar Colloquies (1518).

His most outstanding contribution both to scholarship and to the future course of church history was his publication of the Greek New Testament (1516), in which he applied humanist rules of textual criticism to the extant Greek biblical manuscripts of his day, accompanied by a new Latin translation directly from the original language and by notes. As a result, scholars were now in a position to make accurate comparison between the New Testament church and the church of their day, with the assessment decidedly unfavorable to the latter.

A necessary complement to the work of Erasmus, Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) expanded the humanistic brand of scholarship to the Jewish Bible; in 1499 this prince of German humanists traveled to the Jewish community in Bologna to study Hebrew language, literature, and theology under the Jewish rabbinic scholar Obadiah Sforno.

The fruit of Reuchlin’s scientific study of the Christian Old Testament was his 1506 Of the Rudiments of Hebrew, a combined Hebrew dictionary and grammar, which enabled others to study the text in its original tongue. The humanist enterprise also spread to Spain through Jiménes de Cisneros (1436–1517), a former resident of the papal curia in Rome.

He established the University of Alcala both to train clergy in the Bible, establishing a trilingual college to provide the classical Latin, Greek, and Hebrew instruction that humanists like Erasmus regarded as essential for any sound theology, and to form virtuous character grounded in earnest Christian piety.

The ideals of Italian Renaissance architecture took root in France under King Francis I, when Italian architects and artisans were invited to France for renovations and new building projects for the king. Deciding to make his Fontainebleau Palace into a center for the arts in the 1530s, Francis invited two Italian interior designers, Giovanni Rosso and Francesco Primaticcio, to create a new style of decoration using a mixture of painting and high-relief stucco molding known as strapwork.

This new technique created a dramatic effect in a long gallery room in Fontainebleau known as the Gallery of Francis I. Francis also embarked on major building projects at châteaux Blois and Chambord, both designed in an Italian Renaissance style adapted to French taste with steep roofs, clusters of tall chimney pots, and the placing of vast elongated windows above one another.

Clement Janequin (1485–1560), who developed the Parisian chanson as a vocal ensemble form, made significant developments in music during Francis’s reign. His approximately 300 chansons are programmatic works, where the musical setting narrates the text using sound effects, such as battle noises, and imitations of natural tones, such as bird calls, to augment the effect of the story.

When social dancing became a prevalent form of entertainment, composers were commissioned to write instrumental music to accompany the dances. In the 1589 treatise Orchesographie, a French priest writing under the pseudonym of Thoinot Arbeau (1519–95) designed two broad dance categories arranged for fife and drum, haut (fast and lively) and bas (slow and stately). Most famous was the gagliard dance from the haut category, featuring a quick duple rhythm with each beat divided into three subunits.

Artistic cultivation found its most fertile soil north of the Alps in the Low Countries and Germany. For example, Geertgen tot sint Jans (1465–93), a monastic painter from St. John in Haarlem, fashioned his famous Virgin and Child, where the figures are completely encircled by a wreath of smaller figures and objects, including several popular musical instruments.

One of the leading Flemish mannerist painters was Pieter Bruegel (1525–69), who developed the ideal of “realism toward the peasants,†in which nonaristocratic figures and objects were rendered in flat areas of color without extensive attention to detail or modeling of human figures.

Bruegel remains remembered for his scenes of peasant life illustrating many aspects of their dress, customs, and forms of entertainment. His paintings were often concerned with disclosing how biblical themes are revealed in the everyday world, as portrayed by his The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind, which shows the helplessness of afflicted peasants.

The German painter Hieronymus Bosch (1453– 1516), who reflected the widespread pessimism of his age provoked by the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War, devised the style of mannerist fantasy. This cynicism transferred over into Bosch’s theological deliberation, fueling his fiery preaching against the evils of the world.

Observing animal instincts, appetites, and the evil of overindulgence in humanity, Bosch attempted to warn his contemporaries through his art, renowned for its overwhelming detail and morbid quality, that, save for repentance, salvation lay beyond their reach.

To this end, his Seven Deadly Sins depicts its human subjects, engaged in folly and gluttony, as pitiable and foolish, and his Concert within the Egg, in a paradoxical depreciation of a related art form, casts music in a diabolic light by depicting several persons standing inside a broken eggshell singing a profane song.

This low view of music is shared by his best-known altarpiece, Garden of Delights, a triptych exhibiting scenes of a highly moralistic nature where musical instruments, such as the lute, harp, hurdy-gurdy, bombard, fife, cornet, and drum, serve as instruments of torture for lost souls in hell who had used music for immoral purposes during their earthly lives.

At the same time, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) grew distinguished for his masterful woodcuts that perfected the technique of crosshatching, where a fine gridwork of lines would be employed in creating light and shadow effects.

Two additional German artists of note were Mathias Grunewald (1460–1528), whose Isenheim Altarpiece depicts the birth, Crucifixion, and Resurrection of Jesus using medieval symbolism and a harsh realistic style, and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543), known for his ability to capture the character and personal attributes of his human subjects.

In both northern and southern Europe, the Renaissance generated lasting effects in the social and religious realms. Looking back to the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome as furnishing the paradigms for humanity’s greatest achievements, much of the literature and fine art produced in this period depicted humanity as beautiful and godlike and exhibited tremendous concern with the emotional life.

While the ideal of the person as an independent entity with the right to develop according to individual preferences undermined the medieval ideal of one who was to be saved by assuming a humble role in the corporate hierarchy of the church, the return to and scientific study of the primary sources of antiquity made possible a far more accurate knowledge of the Bible. Both of these somewhat divergent factors contributed to the Reformation, with its critique of medieval religion and exaltation of Scripture over tradition.

In the political realm, the rhetorical models of Cicero displaced the perceived scholastic logical wrangling of Aristotle, facilitating improved communication, centralization of power, and administrative effectiveness among the aristocrats of Italian city-states and the rising nation-states of northern Europe. For all its achievements, Renaissance culture stands as one of the primary creative foundations of the modern Western tradition.

- Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni Leonardo Bruni was one of the foremost humanists of the early 15th century in Italy. He dedicated himself to a career of studying and writing about classical Greek and Roman culture and drawing lessons from the era of the Roman republic...

- Donatello

Donatello Donato di Niccolode Bettto Bardi (Donatello) is one of the greatest and most famous Italian sculptors of the 15th century, whose work was greatly influenced by the early European Renaissance. He was born in Florence (or in its vicinities) between...

- Giotto Di Bondone

Giotto di Bondone The early life, artistic training, and attributed works of Giotto di Bondone (commonly referred to as Giotto) are all shrouded in mystery and legend. In his Lives, Vasari provided the first biography and chronicle of the works of Giotto....

- Humanism In Europe

Humanism in Europe Humanism originated in 14th-century Europe as a movement to recover the culture of the ancient Greek and Roman pagans. The term derived from the identification of ancient pagan texts as “human†rather than divine like the...

- Western Civilization Core Course

Western Civilization Core Course. This site is available as both a timeline and index. It includes a survey of history, culture, and ideas with readings, period introductions, and articles. It was created by the History Department at Whitworth College....

World History

Italian Renaissance

|

| Italian Renaissance |

It reached its zenith in the late 15th century prior to its dissolution, aggravated both by an ecclesiastical backlash against its perceived secularism and sensuality and by the series of Italian Wars, or foreign invasions against Italy, starting in 1494. The Renaissance fervor was not to be extinguished, however, as its ideals migrated northward to France, then to the Low Countries and Germany, and finally to England and Scandinavia by the close of the 16th century.

Most common people of the time were unaffected by these innovations and did not view their age as distinctive. Producers of its main aesthetic streams, such as authors, artists, and their patrons, willfully rejected the culture of the preceding era (the Middle Ages) and set out to create a new one.

Sensing only a limited attraction to the courtly motifs of the medieval secular literary tradition and disillusioned by the elaborate argumentation of Scholasticism, the sophisticated urban ruling classes searched for a new culture that would enable them to cope with the quandaries of human existence and empower them to deal with and even manipulate other people.

|   |

Perfectly suited for this aim was the literature of ancient Rome, with its strongly political and ethical outlook and the prominence it placed upon oratorical and rhetorical training. To gain a deeper understanding of Latin literature, the urban elites were quickly drawn to the Greek literature that Roman authors frequently cited and presupposed of their readers as background knowledge. Hence the classical Latin and Greek texts of antiquity served as a common springboard for the era’s multifaceted and interdisciplinary cultural shift.

Social Origins

While formally beginning in the 15th century, the social origins of the Italian Renaissance can be traced back to the economic, social, and political developments in Italian society during the 12th through 14th centuries. The 12th and 13th centuries comprised an age of expansion and prosperity directed by the capitalistic noble classes, or grandi, who often resided in the cities and invested in business but whose cultural traditions were military and feudal, giving preference to the chivalric and courtly literature of France.

This changed in the late 13th century when the nonnoble classes, led by rich businessmen, seized control of many town governments and drove the grandi from power. However the 14th century experienced a series of disasters that, paradoxically, modified the structural foundations of Italian society so as to promote the flourishing of artistic and literary endeavors.

Amidst the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, King Edward III of England disclaimed his debts in 1345, leading to the collapse of the two largest Florentine banks, owned by the Bardi and Peruzzi families. From 1347 to 1350 the Black Death, or bubonic plague, exterminated one-third of Europe’s population, which triggered an economic depression followed by a lengthy period of stagnation. While these events prevented the founding of new fortunes, they left the wealth of established rich families largely intact, creating a new social condition.

Since the relatively high degree of social mobility that kept business enterprise open to new talent and preoccupied with acquiring new wealth had evaporated, the dominant business class was converted from a group of self-made men to a group of men who had inherited their wealth and who had been raised in luxury that they intended to preserve but they could largely take for granted.

Rich businessmen, who retained their active participation in politics to defend their material interests from radical movements spawned by working-class agitation, now devoted an equal amount of time to public affairs, especially the patronage of art and literature.

Looking to Greco-Roman antiquity as a model of administrative effectiveness and intellectual genius, the thinkers, writers, and authors of the age, collectively known as humanists, founded a new approach to scholarship, the mission of which was to restore “true†civilization in place of the prevalent “barbarous†civilization.

This view of history was spearheaded largely by Petrarch (1304–1374), who proceeded to synthesize it with his new anthropology, or doctrine of humanity, that humans were rational and sentient beings, intrinsically good by nature, with the power to think and choose for themselves. With this blatant denial of the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, the humanists provoked fresh insights about reality that questioned the church’s philosophical perception of the universe and the role of humanity within it.

Before the 13th century, Italian was not the language of literature in Italy, as most works were composed in Latin, French, or Provençal. However, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries before the rise of Renaissance humanism, a number of masterpieces in the vernacular catalyzed the transition of Italy from a cultural backwater to the leader of European culture.

The nation’s first great literary figure, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), wrote his magnum opus, La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy), in Italian, which reflected the social and political life of the Florentine people and amassed great popularity.

Petrarch became the second great figure of Italian vernacular literature through poems capturing the attention of both refined courtly society and the common people. The master of the Italian sonnet, Petrarch is best remembered for his highly personal and subjective love poetry, most notably the Canzoniere, a collection of sonnets addressed to his unrequited love, Laura.

The third great figure of 14th century Florentine literature was Petrarch’s disciple, Giovanni Boccacio (1313–75), whose principal work, the Decameron, featured 100 stories recounted by 10 storytellers who fled to the outskirts of Florence to evade the Black Death. His work was heightened by motifs reflecting everyday life, including satire against corrupt clergymen, amusing treatment of human idiosyncrasies, and tales of marital infidelity.

Unfortunately the trend toward classical humanism in the first half of the 15th century temporarily stifled the germination of the vernacular tradition, which deterrence was removed by the major revival of the vernacular in the second half of that century.

Under the influence of Florence’s leading family, the Medicis, Italian resurfaced as a medium for important literary work and came to the fore when Lorenzo de’ Medici, the first of the family educated from an early age in the humanist tradition, formalized Medici rule over the city with his creation of the new Council of Seventy, over which he appointed himself head, in 1469. Lorenzo was a lyric poet of great ability who set the stylistic parameters for both secular and religious poetry in the vernacular.

The Florentine Petrarchan tradition experienced great development under the Venetian cleric Pietro Bembo, a leader in the movement attempting to restore the purity of the Latin language embodied in Cicero, when he embraced its highly refined sentiment and technical mastery of intricate verse forms for his Italian poetry.

Popular literature of a less aristocratic flavor often applied French chivalric and courtly themes to Italian characters. Recasting the French heroic knight into the Italian Orlando, Italian courtiers such as Luigi Pulci (1432–84) adapted this material for consciously humorous verse.

Medieval French chivalric themes were discussed more seriously in the poem Orlando innamorato (Orlando in Love) by Matteo Boiardo (1441–94), a noble at the refined court of the dukes of Ferrara who invented a new style integrating humanistic classical topics with medieval chivalric interests.

This style received further advancement under Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533) in his Orlando furioso (Orlando’s Insanity) and reached its pinnacle in the 16th century with Torquato Tasso (1544–95), whose Jerusalem Delivered, an epic of the Crusades, revamped this popular medieval theme into a major literary production that influenced practically all other 16th-century literature.

The most brilliant example of Italian prose in the High Renaissance (the early 16th century) is the work of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) on politics and history. His two principal books, The Prince and Discourses on the First Ten Books on Titus Livius, drew heavily on the author’s firsthand experience as a leading Florentine diplomat and civil servant in the Florentine republic (1494–1512).

Although The Prince is notorious for its advocacy of political self-seeking through deceitful tactics, Machiavelli regarded a balanced republican government, typified by Rome, as the best and most durable form of government and trusted the public spirit and wisdom of the common citizens more than that of princes and aristocrats.

In the artistic sphere, Giotto di Bondone (1266–1336) took the first steps toward the Renaissance, completely forsaking the flat and nonrepresentational appearance of the prevailing Byzantine art in favor of the illusion of three-dimensional form on the twodimensional painted surface.

He was the originator of “tactile value,†portraying his space as an extension of the real space out of which the spectator looked and giving his figures a three-dimensional depth that appeared as if the spectator could reach in and grasp them. Moreover, each of Giotto’s works features the visual representation of one unifying idea instead of a spectrum of meticulous details.

The Renaissance style in sculpture was created by Donatello (1386–1466), who assimilated the basic principles of ancient sculpture, such as contrapposto (with weight shifted to one leg) and the unsupported nude, into a framework creating the appearance of movement and furnishing accurate anatomical structure of his figures.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) brought this style to maturity with sculptures independent of any surrounding architectural support, including the David and the marble figures he carved for the tomb of Pope Julius II at Rome and for the tombs of the Medici family at Florence.

The striking aspect of his approach is its portrayal of robustness and monumentality in the human body, often styled “Dionysian†after the Greek god known for his unbridled power. His spectacular frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel stand as perhaps the single greatest work of High Renaissance painting, and his redesigning of St. Peter’s crowned his prominence as an architect.

Two other Florentine-trained artists, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520), further defined the High Renaissance style. A universal genius with interests in nature, physics, and engineering, Leonardo is most renowned as a painter, revolutionizing his field with the invention of both atmospheric background and sfumato, the “smoky†effect achieved by blurring the outlines of figures to make them softer with an environment of shadow tones. He experimented greatly with new paints even at the expense of the traditional fresco style, seen most prominently in The Last Supper.

Intensely interested in studying the human personality and portraying it on canvas, Leonardo attempted to capture the fragile, fleeting, and illusive qualities of human facial expressions in his Mona Lisa and Virgin and Child with St. Anne. His plans and sketches proved greatly significant for architecture, as they constitute the blueprints for buildings later erected by his friend Bramante (1444–1514).

Raphael’s images, including his many Madonnas, the School of Athens, and Disputa, rank among the world’s most beloved artistic treasures and are noteworthy for their sense of peace and serenity. Furnishing inspiration in architecture as well as in literature, the ideals of classical antiquity experienced restoration in the work of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72). Brunelleschi’s designs for two Florentine churches, San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito, reflect his intense study of ancient Roman buildings, as both employ the early basilica form and classical columns.

Further he is renowned for his discovery of the mathematical rules of perspective and his innovations in shape, seen most clearly in the octagonally designed dome base for the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Alberti revitalized the ancient brick architecture of Roman times, as portrayed by his San Andrea church in Mantua, and established the Renaissance standard use of flat roofs, overhanging cornices, and prominent horizontal lines.

Ironically 15th century music saw little advancement and primarily continued in the genres conceived by Francesco Landini (1325–97), who despite his blindness from childhood became a leading composer and music theorist. Celebrated as a composer of secular works for voice and accompaniment, Landini developed the ballata, or rhythmic dance song; the caccia, a “chasing†song of enjoyment; and, most importantly, the madrigal, a high art form in which poetry was sensitively set to music and so guaranteed that the music would serve as an appropriate vehicle for conveying the spirit and emotional content of the text.

Italian Renaissance church music reached its zenith during the 16th century in the works of Giovanni da Palestrina (1525–94), choirmaster of St. Peter’s in Rome, who composed more than 600 religious pieces, including 102 masses. Typified by the Agnus Dei from his Pope Marcellus Mass, Palestrina achieved a stunning sense of serenity in his works through balance, purity, and arrangement of texts that made the words clearly understandable during performance.

Early Northern Renaissance

With the free exchange of scholars and students between European universities and political exploits, such as the French invasion of Italy in 1494, which brought new contact between cultural elements, Italian concepts and discoveries were reaching into the rest of the Continent by the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The reorganized and powerful monarchies of the north quickly found that Renaissance thought suited their needs, as its endorsement of social class and military prowess enhanced their status, and its emphasis on public service, personal merit, and learning furnished an attractive substitute for the traditional manners of the uneducated and disorderly feudal classes.

Moreover, the invention of the printing press at Mainz by Johann Gutenberg in 1456 changed the course of history by making possible the rapid dissemination of ideas to a populace moved by the spirit of the age to become increasingly more literate.

Disillusioned by corruption in the late medieval church, including simony (buying and selling of church offices), sinecures (receiving the salary from a benefice, or region to be served by a clergyperson, without overseeing it), pluralism (holding more than one office), clerical concubinage, and the selling of indulgences, the bourgeoisie or rising upper-middle class of merchants found the Renaissance rejection of the recent past and the desire to return to the original sources of antiquity tremendously appealing.

This interest sparked a northern movement of biblical humanism, which exalted ethical and religious factors over the aesthetic and secular ideals typical of Italian humanism and was primarily interested in the Christian past, or Judeo-Christian heritage, rather than the classical Hellenic heritage of Western Europe.

More interested in the human being as a spiritual than a rational creature, these biblical humanists applied the techniques and methods of humanism to the study of the Scriptures. This exegetical approach was spearheaded by John Colet (1466–1519), a pious English cleric who, after visiting Renaissance Italy, soon afterward began in lectures at St. Paul’s Church to expound the literal meaning of the Pauline Epistles, a novelty because former theologians interpreted Scripture allegorically with an almost total unconcern with the meaning originally intended by its authors.

Borrowing his notion of biblical humanism from Colet, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469–1536) became the greatest of all the northern humanists and an internationally renowned scholar. Unlike the later reformers who vehemently denounced the evils in the church, Erasmus’s scholarly spirit inclined him to oppose its abuses through clever satire in his The Praise of Folly (1511) and Familiar Colloquies (1518).

His most outstanding contribution both to scholarship and to the future course of church history was his publication of the Greek New Testament (1516), in which he applied humanist rules of textual criticism to the extant Greek biblical manuscripts of his day, accompanied by a new Latin translation directly from the original language and by notes. As a result, scholars were now in a position to make accurate comparison between the New Testament church and the church of their day, with the assessment decidedly unfavorable to the latter.

A necessary complement to the work of Erasmus, Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) expanded the humanistic brand of scholarship to the Jewish Bible; in 1499 this prince of German humanists traveled to the Jewish community in Bologna to study Hebrew language, literature, and theology under the Jewish rabbinic scholar Obadiah Sforno.

The fruit of Reuchlin’s scientific study of the Christian Old Testament was his 1506 Of the Rudiments of Hebrew, a combined Hebrew dictionary and grammar, which enabled others to study the text in its original tongue. The humanist enterprise also spread to Spain through Jiménes de Cisneros (1436–1517), a former resident of the papal curia in Rome.

He established the University of Alcala both to train clergy in the Bible, establishing a trilingual college to provide the classical Latin, Greek, and Hebrew instruction that humanists like Erasmus regarded as essential for any sound theology, and to form virtuous character grounded in earnest Christian piety.

The ideals of Italian Renaissance architecture took root in France under King Francis I, when Italian architects and artisans were invited to France for renovations and new building projects for the king. Deciding to make his Fontainebleau Palace into a center for the arts in the 1530s, Francis invited two Italian interior designers, Giovanni Rosso and Francesco Primaticcio, to create a new style of decoration using a mixture of painting and high-relief stucco molding known as strapwork.

This new technique created a dramatic effect in a long gallery room in Fontainebleau known as the Gallery of Francis I. Francis also embarked on major building projects at châteaux Blois and Chambord, both designed in an Italian Renaissance style adapted to French taste with steep roofs, clusters of tall chimney pots, and the placing of vast elongated windows above one another.

Clement Janequin (1485–1560), who developed the Parisian chanson as a vocal ensemble form, made significant developments in music during Francis’s reign. His approximately 300 chansons are programmatic works, where the musical setting narrates the text using sound effects, such as battle noises, and imitations of natural tones, such as bird calls, to augment the effect of the story.

When social dancing became a prevalent form of entertainment, composers were commissioned to write instrumental music to accompany the dances. In the 1589 treatise Orchesographie, a French priest writing under the pseudonym of Thoinot Arbeau (1519–95) designed two broad dance categories arranged for fife and drum, haut (fast and lively) and bas (slow and stately). Most famous was the gagliard dance from the haut category, featuring a quick duple rhythm with each beat divided into three subunits.

Artistic cultivation found its most fertile soil north of the Alps in the Low Countries and Germany. For example, Geertgen tot sint Jans (1465–93), a monastic painter from St. John in Haarlem, fashioned his famous Virgin and Child, where the figures are completely encircled by a wreath of smaller figures and objects, including several popular musical instruments.

One of the leading Flemish mannerist painters was Pieter Bruegel (1525–69), who developed the ideal of “realism toward the peasants,†in which nonaristocratic figures and objects were rendered in flat areas of color without extensive attention to detail or modeling of human figures.

Bruegel remains remembered for his scenes of peasant life illustrating many aspects of their dress, customs, and forms of entertainment. His paintings were often concerned with disclosing how biblical themes are revealed in the everyday world, as portrayed by his The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind, which shows the helplessness of afflicted peasants.

|

| renaissance painting |

The German painter Hieronymus Bosch (1453– 1516), who reflected the widespread pessimism of his age provoked by the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War, devised the style of mannerist fantasy. This cynicism transferred over into Bosch’s theological deliberation, fueling his fiery preaching against the evils of the world.

Observing animal instincts, appetites, and the evil of overindulgence in humanity, Bosch attempted to warn his contemporaries through his art, renowned for its overwhelming detail and morbid quality, that, save for repentance, salvation lay beyond their reach.

To this end, his Seven Deadly Sins depicts its human subjects, engaged in folly and gluttony, as pitiable and foolish, and his Concert within the Egg, in a paradoxical depreciation of a related art form, casts music in a diabolic light by depicting several persons standing inside a broken eggshell singing a profane song.

This low view of music is shared by his best-known altarpiece, Garden of Delights, a triptych exhibiting scenes of a highly moralistic nature where musical instruments, such as the lute, harp, hurdy-gurdy, bombard, fife, cornet, and drum, serve as instruments of torture for lost souls in hell who had used music for immoral purposes during their earthly lives.

At the same time, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) grew distinguished for his masterful woodcuts that perfected the technique of crosshatching, where a fine gridwork of lines would be employed in creating light and shadow effects.

Two additional German artists of note were Mathias Grunewald (1460–1528), whose Isenheim Altarpiece depicts the birth, Crucifixion, and Resurrection of Jesus using medieval symbolism and a harsh realistic style, and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543), known for his ability to capture the character and personal attributes of his human subjects.

In both northern and southern Europe, the Renaissance generated lasting effects in the social and religious realms. Looking back to the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome as furnishing the paradigms for humanity’s greatest achievements, much of the literature and fine art produced in this period depicted humanity as beautiful and godlike and exhibited tremendous concern with the emotional life.

While the ideal of the person as an independent entity with the right to develop according to individual preferences undermined the medieval ideal of one who was to be saved by assuming a humble role in the corporate hierarchy of the church, the return to and scientific study of the primary sources of antiquity made possible a far more accurate knowledge of the Bible. Both of these somewhat divergent factors contributed to the Reformation, with its critique of medieval religion and exaltation of Scripture over tradition.

In the political realm, the rhetorical models of Cicero displaced the perceived scholastic logical wrangling of Aristotle, facilitating improved communication, centralization of power, and administrative effectiveness among the aristocrats of Italian city-states and the rising nation-states of northern Europe. For all its achievements, Renaissance culture stands as one of the primary creative foundations of the modern Western tradition.

- Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni Leonardo Bruni was one of the foremost humanists of the early 15th century in Italy. He dedicated himself to a career of studying and writing about classical Greek and Roman culture and drawing lessons from the era of the Roman republic...

- Donatello

Donatello Donato di Niccolode Bettto Bardi (Donatello) is one of the greatest and most famous Italian sculptors of the 15th century, whose work was greatly influenced by the early European Renaissance. He was born in Florence (or in its vicinities) between...

- Giotto Di Bondone

Giotto di Bondone The early life, artistic training, and attributed works of Giotto di Bondone (commonly referred to as Giotto) are all shrouded in mystery and legend. In his Lives, Vasari provided the first biography and chronicle of the works of Giotto....

- Humanism In Europe

Humanism in Europe Humanism originated in 14th-century Europe as a movement to recover the culture of the ancient Greek and Roman pagans. The term derived from the identification of ancient pagan texts as “human†rather than divine like the...

- Western Civilization Core Course

Western Civilization Core Course. This site is available as both a timeline and index. It includes a survey of history, culture, and ideas with readings, period introductions, and articles. It was created by the History Department at Whitworth College....